Guest Editorial

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.25071/2292-4736/37675Abstract

Full Text

As this edition of Undercurrents is poised to print, an online CBC article reports the top ten things visitors will not see in Beijing during the Olympic Games. The government is in the midst of a crackdown to manufacture what they believe is a more acceptable China, or perhaps more precisely, a more acceptable China to Western eyes. Number one is rain.1 After “rowdy fans” and “pushing and shoving” is “dog meat.” Not only will dog meat not appear on restaurant menus, but regular patrons will also be actively discouraged from ordering any canine-related cuisine during the Games.

Of the CBC list, the dog meat entry has prompted the greatest deluge of website feedback. A brief sampling: “Say what you will about culture, I still don’t like the idea of dogs for food. At least in North America, our animals are killed somewhat humanely…”; “It is ridiculous for us to judge the Chinese harshly for eating dogs as food when we slaughter thousands of animals every year to fill our bellies in North America”; “People rarely eat dog here. It is actually a Korean thing”; “As for dog... a little gamey but delicious! Don’t knock it ‘til you’ve tried it!” and finally, “Ace work fact-checking, CBC - that [accompanying] photo of [the] ‘dog meat’ [protest] was taken in Korea.”

There are many important queries to pose about the CBC story, featured picture, and resultant commentary. We might immediately raise questions related to nationalism, colonialism, xenophobia, food politics, racism, technology, spectatorship, and animal welfare, among others. Perhaps the more challenging exercise is to consider how these discourses might intersect in complex and layered ways. Even that is not enough, though, as the discourses we use to analyze phenomena are rife with their own suppositions. For example, how does one become a food animal? In which ways do dominant discourses of nationalism preclude the possibility of animal nations? How does “animal welfare” assume the property status of animals and an orientation toward “humane” care rather than industry abolition? In the Academy and society more broadly, we are learning to ask better questions, to question the discourses themselves, and to call out the unmarked categories as the tenuous and contradictory constructions they are.

Chief among these pursuits for Animal Studies scholars are efforts to de-center the human subject (e.g., Baker, 1993), that is, to both reveal the human subject as a historically and culturally-mediated construction, and to simultaneously reposition animals as subjects. For many, such a shift is paired with the desire to realize what Sallie McFague (1997) describes as "subject-subjects relations." In her article, "Becoming (more-than) human, Nicole Bonner addresses this notion as part of her inquiry into the the colonial and gendered roots of the concept of "human," suggesting that a continual interrogation of how we understand that category opens up a more ethical position from which to act. In relation, a great deal is missed (and many negative consequences reaped) when our analyses fail to acknowledge animals beyond their metaphorical uses, or when we treat them simply as blank canvasses to splash own desires and fears against These are not minor topics. As Jody Emel and Jennifer Wolch (1998) contend, “As the frontier between civility and barbarity, culture and nature increasingly drifts, animal bodies flank the moving line. It is upon animal bodies that the struggles for naming what is human, what lies within the grasp of human agency, what is possible are taking place” (p. 19). Consider, for example, Akira Mizuta Lippit’s contention (this issue) that Western human subjectivity is, as of the late 1950s, haunted subjectivity. That is, the human subject is haunted by animals and all excluded Others. The self-assuring phrase, “It’s only an animal,” does not hold. Animals return our gaze; they assert their presence and their subjectivity.

Following Donna Haraway (1991, 2003), an appreciation of specificity and partial perspective is crucial. As more critical understandings of dominant Western human subjectivity are generated, there must be a simultaneous acknowledgement of the multiplicity of subjectivities and cultures, both human and nonhuman, which are reproduced and negotiated in particular places, at particular times. For example, Gavan Watson shows this in his attention to the interlaced multiple meanings of “the Barn Owl”, specifically as related to a controversial photo that appeared in an Ontario birding community one fated winter. Adjacently, Rachel Forbes, in her investigation of the possible place of animals within Aboriginal legal systems, contrasts such renderings against those of traditional Western jurisprudence. Without such engaged orientation, we are prone to regard Others as abstractions, comfortable in the false sense of security that these categories can afford; we potentially elide meaningful differences and remain starkly ignorant of past and present lived experiences, while leaving ourselves largely unmoved and unchanged.

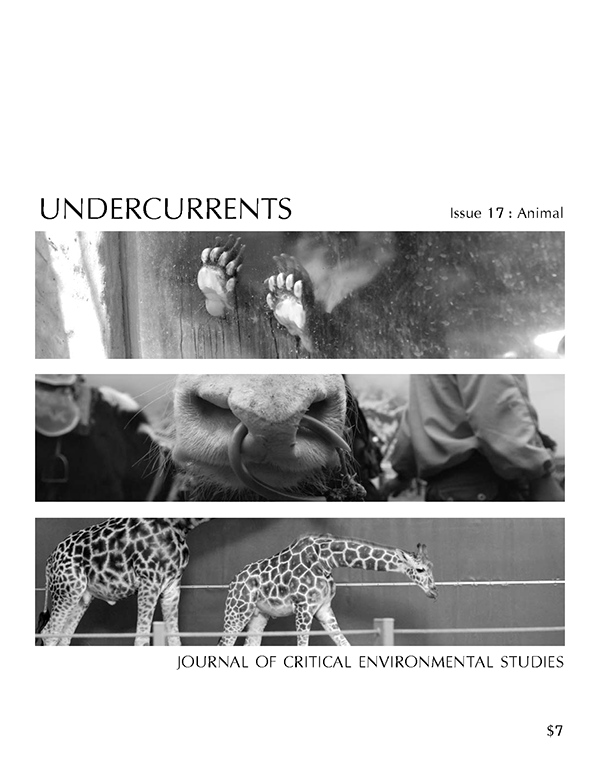

This issue of Undercurrents is an invitation. Like the featured photography of Jo-Anne McArthur, which draws us deeper into its subjects, these pieces offer entry points into future discussions. In these offerings, UnderCurrents invites readers to open more spaces where “the question of the animal”, and its various human and nonhuman interlocutors, may flourish.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2013 Lauren Corman

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Authors retain copyright over their work and license their work for publication in UnderCurrents under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). This means that the work is available for commercial and non-commercial use, reproduction, and adaptation provided that the original authors are credited and the original publication in this journal is cited, following standard academic practice.